3: Chinatown is Nowhere

A ‘Chinatown’ is a funny thing. They are distinct neighbourhood when a city is appended to it, such that ‘London Chinatown’ or ‘Chinatown, Singapore’ or ‘Manhattan Chinatown’ of course refers to a specific place, often down to precise delineations unlike the blurred boundaries of, say, Harlem/Manhattan Valley/Morningside Heights/Upper West Side.

Yet a ‘Chinatown’ is also a racial signifier, an idea that seems to untether itself from a city’s wider history and spatiality such that its own history becomes one of contrasts – where an authentic culture resides amidst the modernizing flux of another downtown, where real food at real prices can be found, in sharp contrast to the clientele of its gentrifying foil, the ‘third space’ coffeeshop, where a distinct cultural group resides in contrast to the blended, heterogenous, multicultural mass of a metropolis, all within the distance of a short walk or skip and a hop on the subway.1

Consider the ‘chopstick fonts’ that postcard illustrators, bastions of respectful cultural representation, seem unable to let go off when illustrating Chinatown. This is typography I still encounter when I get a box to take back a heaping mass of leftovers from Sichuanese restaurants in Flushing.

‘Chopstick Font’ postcard. 2

I will find the exact same postcard early on in the box of the NYPL, a testament to the mass production and circulation of this one specific image. Sometimes these postcards exhibit some degree of verisimilitude. I notice “Mon Fong Wo Co.” appearing time and time again on the intersection of Mott Street and Pell Street, where it does not exist today: a brief mention of it as the “Mon Fong Wo Company. 36 Pell Street, corner Mott Street. The ultimate Cantonese supplier” hint at what these cards capture, but the thin line between orientalist squiggles and documentation. Another postcard from the Brown Bros is undated, but those within sport queues suggestive of Qing-era, pre-1911 China:

Chinatown “Presents many strange sights and many a point of interest who has a little leisure time to wander through the quaint streets and visit the stores filled with all sorts of fancy wares from the Orient… While the appearance of the buildings and surroundings is somewhat arrayed in typically Chinese or Oriental style, the mode of living and appearance of the Chinese people show little change from their accustomed native ways.” 3

The Museum of the City of New York’s exhibit on Art Deco City: New York Postcards offers a tour of New York City – a “cosmopolitan metropolis: a center of architecture, design, fashion, and culture stealing the spotlight from the great European capitals”. It would be unfair to wish an exhibit into something that it was not, but this element of the cosmopolitan has always been defined in architecture, and more recently, starchitecture, in contrast to the enclaves sandwiched between, say, midtown’s skyscrapers and the civic center’s impressive federalist and renaissance revival architecture. Exiting Canal Street, glimpses of the imposing municipal core astound me, the municipal seat of power just steps away. This is the New York that seems destined for postcards, although even these depopulated, (over)designed clearly bear their own fiction.

I find that an older generation of postcards assert their own territory, offering another marker of Chinatown’s boundaries beyond the earlier semiotic universe of signage. Take this account from one:

“The heart of Chinatown is on Mott Street, from Bayard to Chatham Square. On this street and the immediate neighborhood live the majority of the Chinese in New York City. Here are located the joss houses, the civil officers of the colony and lodging houses and restaurants, the gambling rooms and opium-smoking dens. The Chinese stores containing mostly goods imported direct [sic] are always open to visitors.”

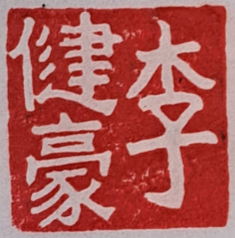

There, street signs and the architecture seem rendered well – photographs hand-painted possibly – against crudely painted Chinese figures standing around, all in dramatically less detail and their queues poking out from under their Western-style hats. What I am viewing are 1940s/1950s-era postcards, many of which can be found inexpensively on eBay; occasionally some of these illustrators have taken a crack at reproducing Chinese characters to comical effect. Elsewhere the hand of someone actually Chinese is present; presumably a shop proprietor has written the characters for ‘Good Luck’. The same font appears in the campaign poster of C. C. O’Donnell, the President of the Anti-Coolie club who ran in San Francisco, home to North America’s oldest Chinatown, on the promise to deport all Chinese immigrants within a day of being elected.4

- In New York, I wonder if the same comparison could be drawn to, say, Spanish Harlem or Jackson Heights, but their historical trajectories have differed greatly. ↩︎

- Ephemeral listing of one such postcard; eBay. “1950 NY Postcard Greetings from Chinatown New York Vintage Linen Stores Street.” Accessed April 6, 2025. https://www.ebay.com/itm/334533982354.

↩︎ - “Art Deco City: New York Postcards from the Leonard A. Lauder Collection.” Accessed April 19, 2025. https://www.mcny.org/exhibition/art-deco-city-new-york-postcards-leonard-lauder-collection. ↩︎

- Cheng, Alicia Yin. This Is What Democracy Looked like: A Visual History of the Printed Ballot. First edition. New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 2020, p. 176 ↩︎

Leave a Reply